A One-Question History Test

Every now and then, a high school or college professor will write an especially difficult exam beginning with “You will have one hour to complete this test. You must remain at your desk until the hour has ended. Read the entire exam carefully before beginning to write your answers.”

It’s a trap. It would be impossible to complete the exam in the allotted time, but the last question is always a giveaway – something like “Only answer this question: What’s the name of this course.”

In that spirit, here’s an American History test: “De facto, slavery in the United States ended with which statement and on what date?” [We’re letting you fudge by combining the two.]

“I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves,

are, and henceforth shall be free.”

Abraham Lincoln.

The Emancipation Proclamation

January 1, 1863

“Neither slave nor involuntary servitude,

except as a punishment for crime

whereof the party shall have been duly convicted,

shall exist within the United States,

or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

The Thirteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States

passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864 and

passed by the House of Representatives on January 31, 1865

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance

with a proclamation from the Executive

of the United States, all slaves are free.

This involves an absolute equality of personal rights

and rights of property between former masters and slaves,

and the connection heretofore existing between them

becomes that between employer and hired labor.

Union General Gordon Granger

June 19, 1865 (Juneteenth)

Galveston, Texas

The “trick” is in the first two words: De facto. Latin for “from the fact” - what happens in reality or in practice.

Slavery in American did not end with Lincoln’s Proclamation, the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment or Granger’s declaration in Texas – the last state in which Lincoln’s order was published.

The Amendment afforded slave-owning and just-plain-corrupt Southern legislators and landowners and Northern corporations a loophole: “…except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted….”

Scholars and prison reform activists have linked the “exception clause” to the rise of a national prison system that incarcerates Black people at more than five times the rate of white people, and profits from their unpaid or underpaid labor.

In the years following the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, “black codes” created new criminal offenses, especially attitudinal offenses – not showing “proper respect” for whites, loitering, vagrancy, and “malicious mischief.” The criminal justice system was deliberately employed to force African Americans into a system of repression and control.

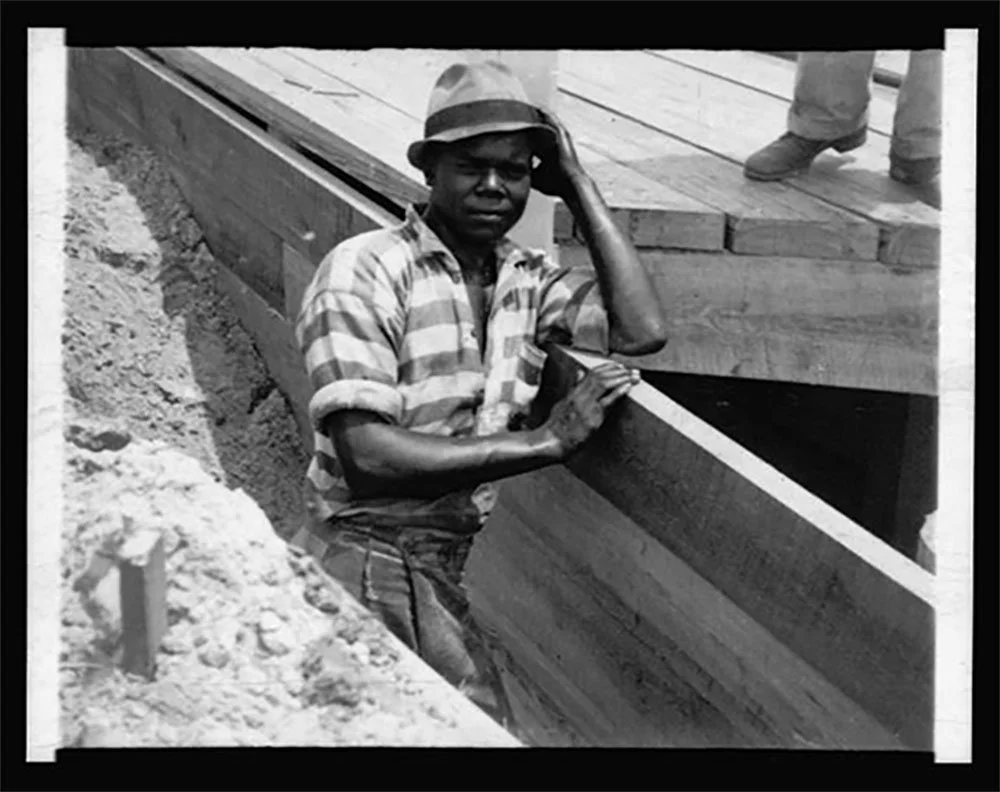

States introduced “convict leasing.” Black and white prisoners were “leased” to planters and industrialists. Convict leasing began in Alabama in 1846 – before the Civil War and when most convicts were white; by 1898, 73 percent of the state’s revenue was generated by “leasing” Black Americans – mostly former slaves. In 1871, the Virginia Supreme Court ruled that a convicted person was “a slave of the State.”

Cheap convict labor also suppressed the developing movement for labor unions. As a result, it worked “just fine” for the white upper class. For many former slaves, convict labor was worse than slavery; slave owners might be reluctant to destroy their “property” but a gang boss could face little or no punishment for murdering a felon – “If he dies, get another.”

Beginning in Mississippi and South Carolina in 1865, the “black codes” were designed to allow white landowners to control the labor force through a system similar to slavery. In Mississippi, Black people were required to have written evidence of employment for the coming year each January; leaving before the end of the contract could result in forfeiture of earlier wages and/or arrest. In South Carolina, Blacks were prohibited by law from holding any occupation other than farmer or servant unless they paid an annual tax of $10 to $100.

Minors throughout the South – either orphans or those whose parents were deemed by a judge to be unable to support them – could become the unpaid labor of white planters.

Black codes were white Southerners’ way of ensuring their supremacy and the survival of plantation agriculture.

The “Black codes” and prisoner leasing were purposeful and profit driven. During slavery, the number of Black people in Tennessee prisons rarely exceeded five percent. Twenty-five years after emancipation with convict leasing flourishing, the percentage of Black prisoners skyrocketed to 75 percent.

The Black codes were designed to control the behavior of African Americans and their ability to engage in gainful employment, earn wages, purchase and own land, move from job to job, assemble in even small groups, terminate labor contracts or testify in courts.

Black codes were designed to provide a new form of slave labor – labor sentenced to steel mills, coal mines and plantations for the enrichment of plantation owners and corporations like Tennessee Road, Iron & Railroad Company and U.S. Steel. Under the Black codes, Black lives did not matter.

On November 25, 2023, Associated Press reporters Margie Mason and Robin McDowell in collaboration with Reveal, a production of the Center for Investigative Reporting, explored the history of Tennessee’s Lone Rock Stockade, where people as young as twelve worked under inhumane conditions in coal mines and coke ovens to produce steel – enriching the Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Company – at the cost of prisoners’ lives. In 1907, U.S. Steel, one of the first companies listed on the Dow Jones Index, took over TCI&R and continued to use prison labor for at least five more years.

The stockade was actually owned by TCI&R and was designed to house 200 inmates at a time. According to the Reveal team, records indicate that by the 1890s the Lone Rock population exceeded 500 and sometimes 600 prisoner-slaves – whites, Native Americas, women and mostly Black men, some twelve to sixteen years old.

Camille Westmont, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in historical anthropology at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee offered Reveal a stomach-churning insight into discipline at Lone Rock, where guards used a whip on naked prisoners:

“It weighs two and a half pounds and it’s made out of shoe leather. So, it’s layers of shoe sole leather that have been bolted together. And the direct quote [from records she found in Tennessee state archives] is, it would be inhumane to whip an ox with this whip, and they’re using it on humans.”

According to Westmont, “These stockades had an annual mortality rate of 10%. Every year, 10% of the people who were imprisoned here died” of tuberculosis, typhoid fever and other deadly diseases. “Some men were killed by cave-ins and falling slate. Others were shot while trying to escape.”

Ultimately, it was not the anonymous deaths of hundreds, perhaps thousands of Black men, women and children on post-Civil War plantations, in coal mines and steel mills that put an end to prisoner leases.

In 2004, Martin Tabert’s nephew described the twenty-two-year old from Munich, North Dakota for a reporter from the Winter Haven [Florida] News Chief: “He wanted to see the world. He saw the bad part of it, I guess.”

In January 1922, Martin Tabert was approximately 80 cents short of the fare he needed. So, he jumped a freight train near Tallahassee, Florida. Because he couldn’t pay the court ordered $25 vagrancy fine, he was sentenced to 90 days in jail and leased out for $25 to help pave a railroad bed for the Putnam Lumber Company in the tiny community of Clara, sixty miles south of Tallahassee. It was part of a lucrative scheme involving Leon County Sheriff J.R. Jones and Judge B.F. Willis to funnel cheap labor to the lumber company.

Suffering from fevers, headaches and oozing sores, Martin Tabert could not keep up on a two-mile march and did not meet his daily quota when Walter Higginbotham, the “whipping boss,” propped him up on his swollen feet and “gave him about 30 licks as Talbert groaned and screamed for mercy,” according to Guard A.P. Shivers. Higginbotham then placed his boot on the youth’s neck and “gave him about 40 or 50 more” and, when Tabert couldn’t get up, gave another 25.

“At first, I heard screams which grew weaker and weaker. Finally, there was only the sound of the lash,” testified Mrs. Walter Lyles, who’d been fishing near the prison labor camp.

Reportedly, Tabert begged for mercy, but was so weak he could hardly talk. Laying unconscious on his bunk, he was left quinine by the company doctor, who diagnosed him as suffering from “pernicious malaria.” He died shortly after 8 p.m., February 2, 1922.

The Panama City [Florida] Pilot headlined the report of his death as “Florida’s disgrace.”

Higginbotham was convicted of second-degree murder and the railroad paid Talbert’s family $20,000.

The Florida legislature, worried about the negative effects the bad publicity might have on the state’s nascent tourism industry, outlawed convict-leasing in May 1923.

But that’s not the end of the story.

In 2022, the American Civil Liberties Union reported that prison workers “employed” in everything from construction work, manufacturing furniture and license plates and doing “stoop labor” farm work had produced close to $11 billion in goods and services but received “just pennies an hour in wages for their prison “jobs.” For example, in New Jersey inmate jobs run the gamut from laundry and kitchen work – which means waking at 4:30 in the morning to begin preparing breakfasts – to medical porters and paralegals. While pay ranges from $1 to $7 a day, most positions pay only $1 to $3 a day and a packet of coffee from the institutional commissary costs $3.45.

“The prisons probably can’t run if the people in prison decided not to work and just took a break,” reports Ron Pierce, who spent thirty years – 1987-2016 - in New Jersey prisons and now works as a policy analyst for the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice. “Nothing works without the incarcerated population — and yet the incarcerated population is being exploited for their labor.”

When Pierce left prison in 2016, he had just $208 in his pocket.

“That’s all I was able to save — in 30 years,” he said.

In June 2023, Senators Jeff Merkley of Oregon and Cory Booker of New Jersey and Rep. Nikema Williams of Georgia introduced the “Abolition Amendment” to abolish the “exception clause” of the Thirteenth Amendment.

“The loophole in our Constitution’s ban on slavery not only allowed slavery to continue, but launched an era of discrimination and mass incarceration that continues to this day,” Merkley told CNN. “To live up to our nation’s promise of justice for all, we must eliminate the Slavery Clause from our Constitution.”

We can hear the objections. “Don’t do the crime if you can’t do the time.”

I, Father Flynn, spent more than eleven years as a chaplain at a maximum-security Florida prison and, while I believe in redemption and change, I firmly believe that there are some men and women in America’s prisons who should never see the light of day as free people because they are just plain bad, maybe genuinely evil.

And, while we abhor trite cliches, we realize – we must all realize – that most of those men and women we’ve locked-up will one day be free.

Nonetheless, it’s time to eliminate the Exception Clause of the Thirteenth Amendment.